Is it possible, by reliving your most painful loss, to come to terms with it?

There are some defeats that linger, some sporting injuries that, like Michael Owen’s hamstrings, seem never to heal. This summer, I decided to poke these old wounds and see if they still ached.

With over 30 years supporting a football team that boasts no league titles and an NFL team that’s never won the Super Bowl, I’ve plenty of defeats to pick from. But it’s easy to choose, isn’t it? You don’t have to draw up a shortlist and carefully whittle it down. You know instantly which they are – the losses that still pain you periodically, returning unbidden like arthritis in winter. Even now they make you wince, the mental equivalent of looking away during the gruesome bit of a horror film.

“I think you’ll be disappointed when you see that one back.”

For me, there’s two. Reading’s defeat in the 1995 Play Off Finals***. I won’t detain you with much about the game; you know how it went: Reading were two up after 12 minutes, missed a penalty for a third before half-time, didn’t concede until the 75th minute and yet ended up losing 4-3 in extra time. To this day, if you say “Two-nil and a penalty” to a Reading fan, a look of sadness will come over their face as if you’ve asked them to remember what it was like when their favourite pet died.

The greatest traumas, of course, are those inflicted in childhood. Hand-me-down clothes. Dead legs and bog-washings. Getting yelled at by teachers. Being picked last at football. And, in my case, the Cincinnati Bengals’ loss to the San Francisco 49ers in Super Bowl XXIII.

It was January 1989 and my newly beloved team were leading 16-13 with just three minutes left. Playing the best team of the 80s, we were poised to win our first ever Super Bowl. But, somehow, we didn’t. Reader, we lost. It finished 20-16 and, nearly 30 years later, we haven’t made it to another Super Bowl. Even accounting for this year’s title match, where the Atlanta Falcons surrendered a 25-point lead with only a third of the game left, it still stands as one of the greatest losses in NFL history.

No sporting event echoes longer in my memory. I cried at the time. I cried the next day. I experienced every one of the rich series of metaphors we’ve developed in sport to describe the acute sensation of defeat.

“There was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black field – my friends watched on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and, as the clock ran out, I sensed an infinite scream passing through Cincinnati.”

As well as being cruel, the defeat was the high watermark for the team. In just of two the next year twenty years would we win more than half of our games. The defeat became a reference point; at the beginning of every season, I would mentally compared the current team with the ‘88 vintage to assess our chances. Are we good enough? Could this be the year?

It wasn’t just an excruciating disappointment, then. It cast a shadow over every game I’ve watched since.

How to conduct your own sporting exorcism

And so, as an experiment, I decided to rewatch it – and to do it properly. If you want to try this yourself, the rules are simple: you have to clear an evening and commit to the whole thing – not just a five-minute highlights reel. You have to get snacks and drinks and, sitting down with complete focus, approach your agonising defeat as if you have no idea of the result and are about to watch a normal sporting event. (Rather than a car crash in which your childhood dreams get crushed under a burning juggernaut.)

After 27 years, would it still hurt, I wondered? Would I have remembered it right? Were the things etched into my memory really the key moments? How much has the game changed? Did my team really deserve to lose?

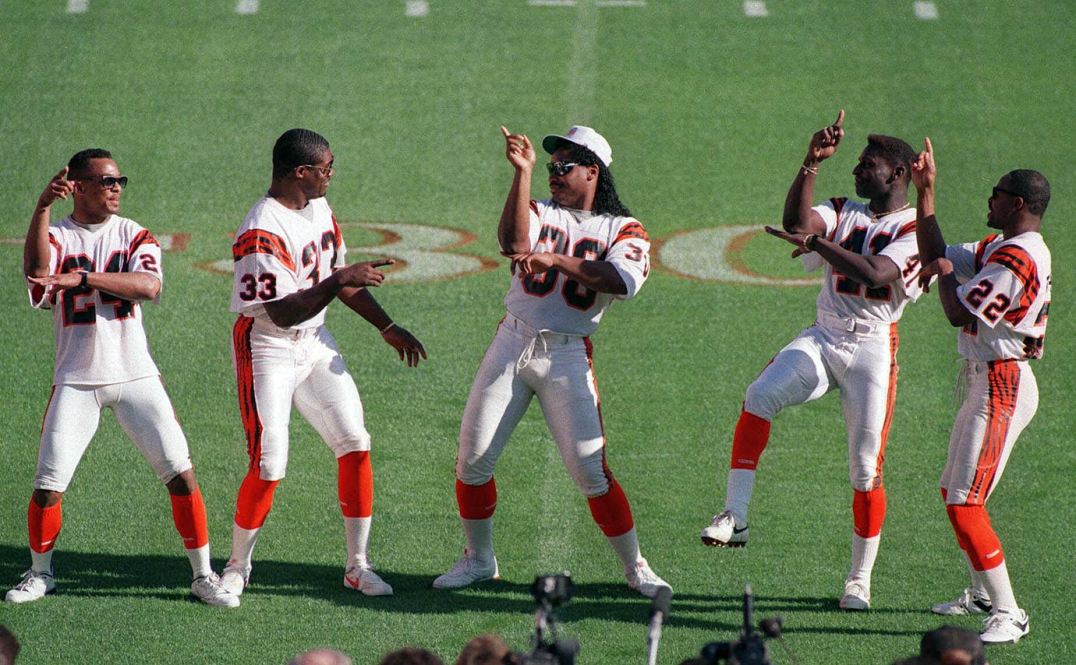

I felt surprisingly light-hearted as I cued up the film. It would be great to see these old legends playing the game of their lives. Boomer Esiason, our star quarterback still cruelly excluded from the NFL Hall of Fame, would be throwing the passes. Anthony Muñoz, as good an offensive lineman as the NFL has ever seen, would be dominating people. Ickey Woods, he of the famed Ickey Shuffle touchdown celebration, would be carrying the ball for us. For a moment, I genuinely thought, “Who knows, maybe we’ll win this time.”

Pre-game mood.

It all changed the moment the game kicked off. As the ball arced high into the Miami sky, I felt overwhelmed with adrenaline-fired anxiety. My hands were shaking and my throat felt like it was closing up. Oh, god, I thought, this was a terrible idea. I’m not ready; it’s too soon. Nerves, it seems, can still get to you after all those years.

Gradually, though, I calmed down and entered a curious state. I was still hyped up for the game – desperate for my team to win – but I was also slightly detached. I was engrossed in the play, but increasingly oblivious to the score. I felt like I was watching the game in slow motion, seeing everything I’d missed first time round.

Like a good novel re-read, there’s new depths to be found in repeat viewings of a sporting event.

You are not an independent observer

For 27 years, my narrative of our defeat was that we were doomed almost from the first moment, when our defensive lynchpin was struck by one of the worst football injuries of all time. I’ve written about Tim Krumrie’s leg before – and the way the story I’d told myself went was like this: against a stronger team, with Joe Montana and Jerry Rice, the greatest quarterback and wide receiver of all time, we’d need our defense to play out of their skin. If we could only hold them to a low score, our offense might carry us over the line. So when Krumrie’s leg was annihilated in the first quarter, I knew we – already the underdogs – were immediately in the realm of needing a miracle. Fate had unforgivably tipped the odds against us.

But something else happen in that first quarter. Something I’d completely forgotten. On just the third play of the game, Steve Wallace, the man protecting Montana, had had his leg broken.

“Good luck, Steve!”

Literally less than a minute into the game, the player whose job it was to ensure Montana had the time to work his magic was carted off the field. Part of what I’d remember as our strong start – a sack, a fumbled 49ers snap – was simply San Francisco struggling to adjust to Wallace’s loss.

You don’t forget the greats, but you do forget the good

Ask someone about Roger Craig and they may say he was a key contributor to San Francisco’s dynasty. A hell of a player, even. But then you watch him rocket past Bengals tacklers and make a mental note to publically apologise for neglecting him for all these years. He was every bit as good a catcher of the ball as they say – there’s a wonderful leaping take on their first possession. Most of all, though, I was shocked by his speed, his power, delivered with an unusually high leg lift, which let him burst through tackles. And there was his swagger – he carried the ball away from his chest, like Shady McCoy, supremely confident in his own body.

71 yards on the ground and 101 in the air.

I didn’t appreciate any of it at the time. Back then, in the heat of battle, he was just an opposition player standing in the way of my team’s deserved victory.

And, on my team, there was David Fulcher, an archetypical head-hunting safety from back in the days when safeties freely endangered lives. “He may be called David,” says the commentator after another shuddering tackle, “but he plays like Goliath.” And he does. At times it seems as if Fulcher is teleporting from place to place, leveling players and then beaming to where the ball will appear next.

In my mind, the Super Bowl had been all about quarterbacks – Montana v Esiason – but, in truth, had the Bengals held on to win, Fulcher would’ve been a deserving MVP, particularly with his forced fumble from Craig which stopped another morale-sapping run. And, with an MVP award on his CV, Fulcher might’ve been talked about alongside the defining safeties of that era. Players like Ronnie Lott of the 49ers, who attacked the day with his customary intensity and was only a few moments of poor luck away from achieving several decapitations during the game.

Ickey Woods’ tacklers wrestle him to the ground, inadvertently saving him from being cut in half by a low-flying Ronnie Lott.

You recognise familiar faces

Sport is a relay race, with the baton continually handed from generation to generation. There, in the background of every big day, are people who will become familiar to you later. And so, as the initial excitement ebbs – and it becomes clear that, far from being the ding-dong battle I remember, it’s actually quite a slow, badly played game – I begin to scan the sidelines.

Dick LeBeau is there, calling plays for Cincinnati. In 2017, he’s 79 and still coaching – nearly 60 unbroken years in the NFL. He’s revered as one of the most influential coaches in history, but back then, to me, he was just the Bengals defensive coordinator.

And Cris Collinsworth is there. The smartest, most articulate commentator on the NFL, who has no parallel in English football, was then – in my mind – no more than a back-up to our star wide receiver Tim McGee. (I was too young to know of Collinsworth’s early career brilliance.) As the game winds down, and with McGee moving poorly after a hit, Esiason turns back to Collinsworth, who repeatedly lays out for some spectacular catches. As I watch the game, I wonder how many of his millions of TV viewers know just how well Collinsworth moved. He has remarkable grace and speed for a man so tall.

When later I look up Collinsworth’s career, I find he retired after this game. I’d been so deep in disappointment, I hadn’t even noticed it was the end of an era. Nearly 30 years on, when asked about having appeared in two losing Super Bowls, both defeats to San Francisco, one in his first season and one in his last, Collinsworth said, “There used to be there wasn’t an hour that went by that I didn’t think about it. Then there was probably not a day that went by I didn’t think about losing those two. Now it’s probably not a week that goes by that I don’t think about it…You always think about it.”

“I’ll be fine. Just give me another decade.”

Collinsworth is a reminder of how much, as fans, we personalise defeat. No one can ever hurt like I hurt about this. We know that players suffer, but we suppose that most of them get over it pretty quickly. They really don’t.

Also retiring that day was Bill Walsh, the 49ers coach who was, until Bill Belichick, the league’s most successful dynasty builder. Pete Rozelle, too, called it a career after 30 years as the NFL commissioner, a period in which he did a much as anyone to build the game into the commercial behemoth it is now.

Your nostalgia isn’t always misleading

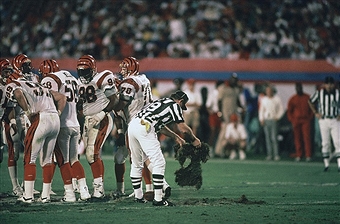

As the game settles into a grim pattern of misplaced Esiason passes and stuttering 49er drives, I experience the warm glow of sport in its more innocent, care-free period. A time when professional athletes could be charmingly out-of-shape and pitches would come apart like a potato field at harvest time.

Impromptu pitch repairs.

At one point, Jim Breech, the diminutive Bengals kicker is called upon to attempt a 34-yard field goal. Missing that kick today would be unthinkable to anyone concerned about his job security, but back then it seemed like a real moment of drama. This is old-time sport at its most comforting. We zoom in on 5’’6’ Breech warming up with tentative leg swings, like a golfer feeling the weight of a new club. “Here comes the man with the smallest foot in pro football,” burbles the commentator. “Size five right shoe… Father of six children.” And then, as the linemen settle into their stances, the pay-off: “It’s a big kick for a small foot.”

Later, when Breech lines up for a 43-yard attempt to put the Bengals up 6-3, the commentator announces gravely that, “This will test the limits of his leg. They like him inside the 40. Outside the 40, it’s a bonus.” In 2016, the NFL’s top five kickers hit 96% of their field goals between 40 and 49 yards. But back in 1989, Breech makes a 43-yarder and the players mob him like he’s just rescued a child from a house fire.

Once more into the Breech. (Tiny foot not shown.)

The half-time entertainment has also come on a long way. This was before the days of the big-name music stars – before Katy Perry’s sharks or Prince’s extraordinary Purple Rain in the pouring rain. But in 1989, just before we go to a break – and after a strong message about home-tapers killing sport – the announcer teases me with, “Coming up at halftime, first half analysis from Bob and Don Shula, our Talent Challenge Results and then ‘BeBop Bamboozled’ in 3-D.”

“Have your 3D glasses ready for the magic show,” he urges. “I checked it out. It’s a fantastic effect. The 3D really works!”

I checked it out too. The show can best be described as what would’ve happened at the end of Footloose if, instead of cutting loose cathartically in a warehouse, Kevin Bacon had dressed as Lincolnshire’s third best Elvis impersonator (over 65s category) and led a thousand deranged Grease fans in a musical tribute to the kind of card trick you get in a Christmas cracker.

I don’t have 3D glasses, so I can’t attest to how effective that part of the show was, but, overall, I definitely enjoyed it more than Avatar.

You see that the greats are great for a reason

There’s a poisonous ‘actually’ argument that says that because sport has improved so dramatically – with coaching, equipment, diet etc – then even the good players of today are superior to the great ones of the past. If you actually dig back into the archives, you are cautioned, you’ll see that they’re nothing special.

But they’re wrong. There was certainly a greater variance then between the good and the bad, but the greats are still like a fireworks display, lighting up the game and filling you with wonder.

Joe Montana was one. He’s masterful as Boomer Esiason, my childhood hero, struggles on a blustery day and repeatedly throws desperately into double and triple coverages. Even by today’s standards, the ball comes out of Montana’s hands quickly. He is playing the game decades ahead of his time. He moves better than you remember, as well, and delivers passes with immaculate rhythm and timing.

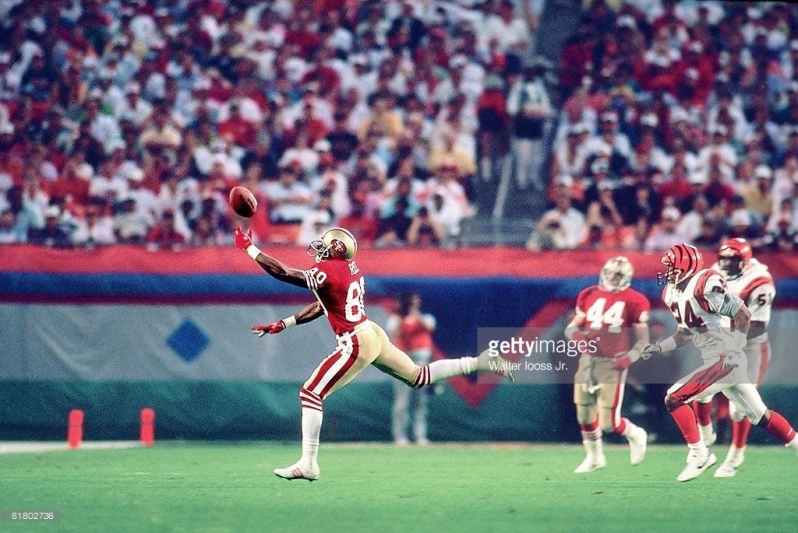

Jerry Rice is wonderful, too – just one dropped pass (one that both you and I would genuinely have caught) from being perfect. There’s a juggled one-handed catch for a crucial first down. There’s the simple beauty of him repeatedly gliding past his DB and, without so much as the tiniest perturbation of his stride, turning to catch the ball as smoothly as if a butler has delivered it to him on a silver salver.

“Ball, Sir?”

“Thank you, I will.”

These people are greats and, even now, it shines out of the grainy game film like a search light on a dark night.

We need to recognise that sport is like culture. The greats of today add to the past, they don’t supersede it. Today’s Booker Prize winner doesn’t make Dickens obsolete. So we should heroise less and rewatch more. The greats shouldn’t be just the stuff of folklore, their memories guarded by tedious pub tale-spinners, nor the subject of cheap talking heads clips shows and 90-second YouTube highlights. We need to blow the archives open. There should be documentary series – The Complete George Best; a 49-parter on Ronaldo’s single season in Barcelona; a director’s cut of every Matt Le Tissier dribble.

Sport is only ephemeral if we let it be.

You know when it’s over

A truly awful defeat often has its pivot point, a single moment that, had things gone differently, would’ve changed the entire outcome. It’s Gazza’s outstretched leg, Stuart Pearce’s missed penalty, Gareth Southgate’s missed penalty, Frank Lampard’s missed penalty, Sol Campbell’s disallowed goal. You get the picture.

In this game it was the Lewis Billups moment.

We’re in the fourth quarter and the Bengals are winning 13-6. The score flatters us, though, because, while the 49ers are on the march, we’re out of steam. I’m exhausted, too. Wracked by tension, unable to sit still and, all the while, a sick dread is growing. I know what’s coming next.

Getting the ball on their own 15-yard line, Montana advances San Francisco 71 yards in just two plays – perfect throws to Rice and Craig. They have the ball on the Bengals 14-yard line. A touchdown here will tie the game, leaving the 49ers ample time to find the winning points and cruise past their spent opponents.

But something goes wrong. Montana sees wide receiver John Taylor driving into the end zone and releases a pass. Lewis Billups, covering Taylor, has seen it too. He cuts inside Taylor and, unchallenged, gets to the ball first. It arrives, as if meant for him, chest height and in-stride. Positioned perfectly, he gets both hands on it. My heart stops. He might catch it this time. Interception! And, if he does, we’ll get the ball back and begin running down the clock, leaving a deflated San Francisco with a mountain to climb.

But he doesn’t. He drops it again. It slips right through his hands and the 49ers get the ball back again. I watch the replay on the film and then rewind it again and again – my only deviation from my plan of watching the whole game in real time. For five minutes I stare as he repeatedly jumps the route and shapes to catch the ball and win the game. The commentator intones pitilessly, “He had it, he had it! You can’t drop that one!”

Lewis Billups (24) has suffered.

Maybe, I tell myself, if I wait another 27 years and try again, then maybe he’ll catch it.

Eventually, I can’t avoid it. I put the game back on and, on the very next play, Montana hits Rice for the touchdown. It’s 13-all – a 14-point swing on one dropped interception. I go into a tail spin. Esiason can’t do anything. We give the ball back and Montana finds Jerry Rice for a stunning 45-yard catch in double coverage. “He’s a human highlights film!” exclaims the commentator. He really is.

We somehow contrive a field goal to retake the lead, but, with three minutes left, the 49ers move 92-yards in ruthless, lockstep precision and score the winning touchdown. We get the ball back again with 26 seconds to go but, by now, even as my 1989 self, I know it’s hopeless. Esiason throws two wild Hail Marys and the game’s over.

We’ve lost. Again.

But hold on… I’m not crying! It feels different this time… I don’t feel completely shattered, stomach balled up in agony. I feel sad, yes, but not angry. It’s worked. I’ve finally accepted defeat.

Truly, it’s an exorcism. The ghosts of 27 years have, if not been completely banished, lost some of their power to haunt me. That desperate, churning desire to change the past has gone. For the first time in nearly three decades, I might be able to face the new season with a clearer perspective and renewed hope.

I might feel different – less freed – if we really had been robbed, but, as it is, I find a curious peace in knowing that we were deservedly beaten. Not only, contrary to my memory, were the Bengals not the best team on the night, but it wasn’t even close. Oddly, though, even that realisation brings solace. This wasn’t a great Bengals team; they weren’t sporting immortals. So, if they could make it to a Super Bowl, then so too might the Bengals of future.

Not for this year, obviously; we’re going to be terrible. But one day, maybe. And when it happens, with luck, I might not have to go through all this again.

So now it’s your turn. Go on, cue up that tape and face your demons. It might be the most important game you watch all season.

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this, please buy my book “The Ugly Game: How Football Lost Its Magic And What It Could Learn From The NFL”. That way I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.

*** In 1994/95, Reading finished in its highest ever league position: 2nd in Division 1. The only reason we didn’t get automatic promotion – for what would’ve been our first ever season in England’s top flight – was that it happened, cruelly, to be the year the Premier League was going down from 22 to 20 clubs. Only two clubs went up – Middlesbrough as champions, Bolton through the play offs – and four teams came down, including Palace, extraordinarily, on 45 points.