With this season drawing to a close, 2015 should be the end of certainty; the year we admit how useless we are at judging quarterbacks and abandon our urge to make final pronouncements on pretty much anyone who’s still taking snaps.

Can we start with some common ground?

Quarterback is the hardest job in professional team sports. Right?

No other position makes such mental and physical demands of a player and has such a disproportionate impact on a team’s performance.

Good so far? Right.

For a variety of reasons, it’s also exceptionally difficult to judge which young players have the right balance of personal and physical talents and to then make consistently useful predictions about how early someone can play, whether they will make it, and how far their talent can carry them and their team. For all the investment in scouting, drafting a quarterback is still, essentially, a coin toss.

All this, with caveats, we know.

And yet still we crave certainty.

Snap judgments and lasting impressions

“Does this have the potential to be a franchise office?” “I’m afraid not. It’s got a low ceiling.”

No phrase in the NFL ecosystem makes my teeth grind like this one: “We know what he is.” Unless, that is, we’re using it as a shorthand to indicate he’s a male human being, probably quite tall, likely somewhere between the age of 22 and 38, and almost certainly American. If we go beyond that – like hundreds of thousands of content creators – then, like Donnie in The Big Lebowski, we’re out of our element. And by ‘element’ I mean ‘our tiny minds’.

How can it be that, with a job freighted with so much uncertainty, so many variables, that we not only want to, but feel confident in putting a grade on a player almost instantly we see tape of him?

The owl of Minerva flies only at dusk, said Hegel, which, for our purposes, means we only know once they’ve retired. Until then, I’d submit, judging a quarterback should be a process of continuous reassessment. One where we seek to develop a more complex, more nuanced view of a player, placing more emphasis on contextualising what he has done rather than seeking to issue public proclamations about what he inevitably will do.

It’s my hope that this season will be the one that makes it so.

A pigeonhole for every player

Draft analyst grades quarterback.

Some people, quite extraordinarily, seem confident about putting a label on a quarterback before he’s even been drafted, as though they are in possession of the NFL equivalent of a Sorting Hat. Others, meanwhile, have the admirable restraint to wait as much as half to three quarters of their first season before reaching for a label from the NFL QB caste system. Solid NFL starter. Future franchise quarterback. Development prospect. Elite. Bust. Potential Hall of Famer.

Aaron Rodgers, for example, began the season as the best in the league, a first-ballot lock for Canton and, according to some, a QB who may end up as the best to ever play the position. To the extent we acknowledge that this was not how he was always seen, we incorporate his late draft plummet and his years warming the bench behind Favre into his story, narrating them as if they were, like Brady’s sixth round drafting, mere bumps on the road to being recognised as the talent he always was. We are much less willing to admit that he has not always been this great and that, for much of the season, he wasn’t. Never mind too that Rodgers takes more sacks than Postman Pat on the train to Pencaster and has, to date, an unremarkable post-season record. (I write this just after he showed signs of life against the Vikes in the playoffs and then delivered a spectacular (if ultimately unimportant) Hail Mary against Arizona – performances that, regardless of how the rest of the post-season plays out, should ensure he begins the 2016 campaign as the consensus best QB in the league.)

If, however, you are inclined to believe that Rodgers’ wobble was prompted largely by a depleted receiving corps and the lack of a dependable running back, let me ask you to consider two draft classes of quarterbacks now coming up to half-way through their careers.

The 2011 and 2012 drafts, the quarterbacks they produced and, most of all, how those players’ reputations have changed this season, will show, I submit, that we still have a long way to go in judging a quarterback’s talent (as distinct from his form) and that our urge to pigeonhole them is at odds with the evidence and is, frankly, ludicrous.

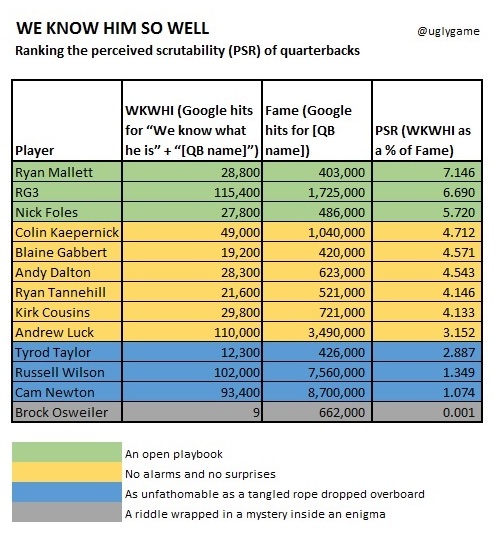

How could we have been wrong, so wrong, about what all these players were? (The bracketed numbers following each player’s name indicate the year he entered the league, the round he was taken in and the number of Google hits returned for “we know what he is” + “[QB name]”. NB: for RG3, I included results for both ‘RG3’ and ‘Robert Griffin III’, as he’s the only player in this article regularly referred to by two distinct names.)

“We know what he is… he’s just a back-up.”

Tyrod Taylor (2011, 6th Rd, 12,300) we knew to be destined to be journeyman back-up, hampered by a lack of height, unspectacular accuracy and a frame too slight to accommodate his propensity to run. In four years backing up Joe Flacco, he’d thrown just 35 passes and there was nothing to suggest he’d ever muscle his way into a starting role, either at Baltimore or anywhere else. And yet watch him in Buffalo this year and he was, by a distance, the most impressive first year starter in the league at QB. He was top 10 in a range of categories, throwing 20 TDs, just 6 interceptions, and displaying sound judgement and a lovely deep ball – as well as those quick legs that we already knew about. Despite being in the league since 2011, nobody, literally nobody, expected this – even when he won a three-way quarterback battle at the start of the season. Yes, he has Sammy Watkins, but who honestly started the season saying, “because he has Watkins to throw to, I expect Taylor to have a breakout year”?

Kirk Cousins (2012, 4th Rd, 29,800) is Tyrod Taylor on a rollercoaster. He was drafted by Washington the same year they went all in on RG3 (2012, 1st Rd, 115,400) and, for a time at least, he looked like an able back-up who’d need a move to get a shot as a starter. Occasionally, when RG3 was injured, he’d show enough that rumours grew a team might trade for him. Is he worth a second, we asked ourselves. But, once he got a proper run in the team, his predilection for throwing interceptions became apparent and he was benched for Colt McCoy – and we all, of course, knew what McCoy was. Suddenly, no-one wanted to trade for Cousins and, with RG3 tagged a bust, Washington was facing a season with nothing at quarterback. Nine wins, a division title and a play-off appearance later, Cousins is one signature away from being set for the rest of his life.

In a piece on players with room for improvement, Bill Barnwell highlighted the single biggest and most extraordinary change. Cousins went from being one of the worst in history at throwing interceptions to being one of the most careful passers in the league. How did he do it? Well, Barnwell, unusually for him, doesn’t have an explanation. Interceptions are bound up, we tend to think, with something intrinsic about how a quarterback plays – how he reads the game, his judgment, his willingness to take risks, his belief in his ability to put the ball into a tight window. As a result, they can seem pretty much immutable; a function of his skillset, mindset and playing style. In Cousins’ case, at least, we were wrong.

Or, at least, it looks that way right now. But then perhaps he’s just this season’s Nick Foles (2012, 3rd Rd, 27,800)? Assuming, of course, that we know what he is.

“We know what he is… he’s an upper second tier quarterback.”

“Won’t you at least let Newton pull on a uniform and show what he can do?” “Sorry. He’s just not an elite reporter.”

Russell Wilson (2012, 3rd Rd, 102,000) and Cam Newton (2011, 1st Rd, 93,400) are phenomenal athletes; one a great scrambler, the other a huge threat on designed runs and third downs. And they both just have that knack, somehow, of winning games. But they’re not prototypical pocket passers, which means, ultimately, they’ll fall short of the highest echelon in the profession: they will never be elite. They also both overly dependent on, it’s suggested, their powerful defences to boost their wins tally.

At least that was the received wisdom at the beginning of the year. (And even, in the case of Newton, the end of the regular season, despite only losing one game. It was, huffed the unimpressed, the weakest 15-1 since Alex James won the celebrity special.)

Leaving aside the pointlessness of the ‘elite’ category – and the respectable arguments to be made that they both comfortably outperformed Aaron Rodgers, one of perhaps two consensus elite quarterbacks, and Andrew Luck (2012, 1st Rd, 110,000), the man knocking at the door – and what you have is two quarterbacks generally recognised as top ten in the league who are now playing at the very highest level. It’s a level above where most people would have said that they belonged at the beginning of the year. Unlike Kirk Cousins, this isn’t two players in receipt of a revelation – they both already knew which team they were supposed to throw to. Rather it represents the outcome of at least three seasons of sustained improvement, improvements that cumulatively represent a qualitative change, I’d argue, in how they should be seen.

Like the extra grains that eventually turn a sandpit into a beach, we need to recognise that Wilson and Newton haven’t just got better and better at doing what they do, but that – and this is Hegel again, observing how, at a certain point, quantitative change become qualitative change – what they are has changed.

Did we see a hint, this season, that Andy Dalton (2011, 2nd Rd, 28,300), the one quarterback about whom everyone has the same opinion, might be about to undergo a similar transformation, albeit from a lower base – from franchise quarterback to top 10? Or was he still the same guy – brittle of confidence and unable to operate with more than half a field – but with a top-level OC?

It will be interesting to see because I distinctly remember, at the end of his first season, one pundit describing him as ‘good enough to win a Super Bowl’. It was meant, I think, as a compliment, whereas now, with a shift of emphasis, people might expand the endorsement to read ‘…like Trent Dilfer did. But only if he can stop choking.’

“We know what he is… he’s a franchise quarterback.”

The value of quarterback investments can, of course, go down as well as up. RG3’s story doesn’t need retelling in any detail, but it’s worth reminding yourself not just how spectacular his debut season was, but that, by any standards, he really can throw a ball very well. Take a look at his numbers not just for his 2012 season but for the injury-plagued 2014 season, where he started just 7 games and Washington went 4-12. They’re really not bad.

And then consider his slightly less gifted counterpart in San Francisco: Colin Kaepernick (2011, 2nd Rd, 49,000). He lacked RG3’s acceleration, improvisation and range of passing, but with the right coaching set-up he went to successive NFC title games.

These two QBs, we knew, were at the forefront of a revolution in how the game was played. But then, against a backdrop of organisational dysfunction, one was hurt, while the other struggled for form.

Our response? Without missing a beat, we realised that they’d been found out. The read-option was a short-lived novelty which was never going to survive the film study of the NFL’s wily old DCs. This ignored, of course, that fact that, in Seattle, Kansas City and Charlotte, designed QB runs and read-option plays continued to prove highly effective for disciplined quarterbacks in stable organisations.

The conclusion I draw about RG3 and Kaepernick, probably going beyond the available evidence, is simply that they had insufficient humility and oversized egos – attitudinal issues that weren’t problematic in college but that may forever hobble them in the high pressure world of the NFL.

The question for me, with RG3 a free agent and Kaepernick in receipt of a head coach with a sympathetic game plan, is whether they can find it in themselves to rebuild their careers and get us to change, yet again, what we think we know about them.

“We know what he is… he’s lucky to be a back-up.”

“It’s okay. I’m a Texans quarterback.”

Blaine Gabbert (2011, 1st Rd, 19,200) has lived, like Brandon Weeden, with what must be one of the worst QB tags to have: the over-drafted figure of fun. Forced too early into the line-up and then labouring with injuries on a terrible team, he didn’t even earn the serious consideration that usually accompanies being a high-end bust. Lampooned and then traded to San Francisco, to a consensus that he wasn’t even fit to be in the league, he began this season in epically low regard. When I googled “Blaine Gabbert” + “we know what he is” the first return was an article entitled: ‘Is the 49ers’ Blaine Gabbert really the worst backup quarterback in the NFL?’ In an unusual twist on the rule that questions in headlines can always be answered ‘no’, this piece concluded gleefully that he was, indeed, the worst QB in the league. And yet anyone who saw him play after Kaepernick’s benching would have to conclude that he wasn’t nearly as poor as he looked in Jacksonville, that he made some good throws and that he was in possession of the most surprising set of wheels since Dick Van Dyke unveiled Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Also ascending into the realm of useful retread was Ryan Mallett (2011, 3rd Rd, 28,800), who began the season as a man-child who could neither operate an alarm clock nor catch a plane. Not just a bust, but a bum. But then Matt Schaub went down injured as Joe Flacco’s back-up, allowing Mallett to go 1-1 with a decent win at home against the Steelers. It should be enough to give Mallett at least another season in the league, while also heralding, finally, the end for the ever-useless Matt Schaub – a QB who holds literally dozens of the Texans’ franchise records.

“We know what he is… he’s a talented QB primed to break out.”

Ryan Tannehill (2012, 1st Rd, 21,600) is, I’d submit, the most remarkable player in this piece. Certainly not because of anything he does on this field but because, to me, he seems to be the QB whose reputation is most immune to reassessment. Even Tom Brady, let us not forget, has been written off before. Yet, no matter how mediocre things are, Tannehill remains a player many believe has talent and is capable, with the right coaching, of being a top QB. Quarterback wins are not everything, of course. But surely they are something? And he’s 29-35 in four seasons, without a play-off appearance and with a rebuilding phase ahead.

Tannehill’s intriguing opposite is Brock Osweiler (2012, 2nd Rd, 9), one of the few players about whom we seem to know almost nothing. And this despite him having started seven games this season, impressed many people and then, without public demur, been benched for Peyton Manning, the once-great quarterback who spent most of the year throwing the ball like a bird with a broken wing.

Perhaps Osweiler, then, is the prototype quarterback of the future. The first of a new bred. The first quarterback about who we can’t say ‘we don’t know what he is…’

We’ll see.

The end of certainty

What can we conclude from this parade of reputational ups-and-downs? Hopefully it’s that, if looking at just two draft classes (accounting for about a third of the league’s starters) shows how much even seemingly settled grades can fluctuate, then we really shouldn’t be so confident in our judgment on quarterbacks.

As sports fans, our assessments of players, teams and coaches seems to be governed by a continuous tug-of-war been confirmation bias (our tendency to seek and give weight only to information that supports our view of something) and our willingness to make hasty generalisations (the snap judgments we make from small sample sizes, a player’s run of goals or TDs etc).

With quarterbacks, though, we seem particularly prone to be first overconfident and then unduly cautious. Once we have a view – and we get one quickly – we stick with it. And look where that gets us.

My intuition is that this flaw is a product of the very fact that judging a quarterback is so hard. I think it’s precisely because we struggle to marshal the ocean of facts and opinions about a player – because we find it hard to give a set of coherent, concrete reasons for our assessment – that our judgment is so impervious to later correction or reassessment.

Whatever the reason, I’d submit, as we run into the start of next season – with returning stars, aspiring journeymen and a new draft class – that when we’re asked ‘What is he? And how good can he be?’ there is only one suitable answer: it’s too soon to tell.

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this, please buy my book “The Ugly Game: How Football Lost Its Magic And What It Could Learn From The NFL”. That way I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.

Pingback: Building a title-winning team: an NFL vs Premier League comparison | The Ugly Game

Pingback: Does Donald Trump have the attributes to be a top NFL quarterback? | The Ugly Game