It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Having rescued their club from ruin at the hands of a string of bad owners, Portsmouth was a club that was going to do things right. But that’s easier said than done when everybody else is still playing fast and loose…

There’s a principle in economics called Gresham’s law that states that ‘bad money drives out good’. Essentially, back when coins used to be made from precious metal, it created an incentive to counterfeit and clip coins, and pass them off as the real thing. If two coins have different amounts of gold in them, but the law treats them as equal, the coins with less gold will soon outnumber the pure.

The same applies to football clubs: bad ownership drives out good. How are fans, even collectively, to find the resources to compete with reckless owners while safeguarding the club for future generations?

Portsmouth will be in League One next year. Given its history and size, its natural home is clearly at least a division higher than that. But it doesn’t have the revenue to compete in the Championship and, with Fratton Park crumbling, England’s largest fan-owned club is at a crossroads – a crossroads with worrying implications for fan ownership.

The concern is this: fans, it seems, can rescue a club, but there’s a glass ceiling. Financing the club so it can compete higher up the leagues seems close to impossible.

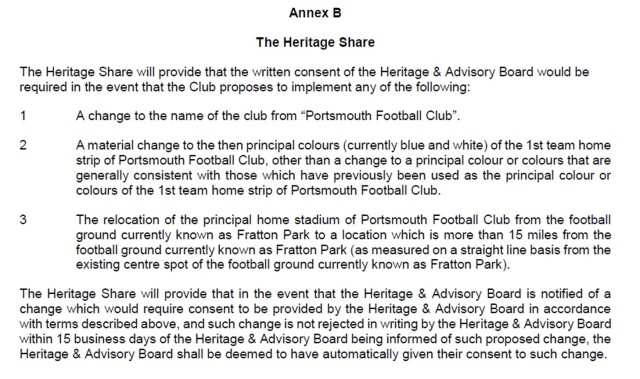

I had a look at the offer document sent to Portsmouth supporter trust members and, for someone who wants to see fan ownership become the norm, it’s a disheartening read. At bottom, fans are being asked if they want to place their trust in someone based largely on his wealth and reputation. Such guarantees as there are cover things like the location of the club and its shirt colours. These are issues with a strong emotional pull, but they don’t address the central question of how to secure the viability of the club for future generations.

Fans are being offered a voice in the club and veto over a limited number of areas.

The prospective owner, Michael Eisner of Disney fame, wants to buy nothing less than 100% of the club. It’s hard to think of an answer as to why this is necessary that’s consistent with the idea of supporters having anything more than a token role in the club’s running.

That’s not to say a better deal was available or that the supporters trust and board haven’t done their utmost to secure the best terms. But this it is not a transaction between equals; Portsmouth need Eisner more than he needs them. And it’s not just that the price isn’t generous, it’s that this is a special form of sale. In essence, Portsmouth fans are being asked to sanction the privatisation of their club.

In essence, Portsmouth fans are being asked to sanction the privatisation of their club.

Embraced so enthusiastically by Mrs Thatcher in the 1980s, when she began the sale of the utilities, railways and social housing, the Portsmouth deal follows the classic pattern. A community asset in need of investment in capital expenditure is bought at below its true long-term value by someone cash-rich. Often, as with the demutualisation of the building societies or the Right to Buy council house scheme, the sellers get a small initial lump sum, but they – and those that follow – pay an increasing amount as customers. Most of all, they lose the right to demand that the asset is run for the common good.

Portsmouth fans certainly can’t be accused of greed; there’s no profit in the deal for them. There’s no doubt, then, that those who vote to sell will do so genuinely believing it’s in the best interests of the club. And they may be right. But there’s no avoiding that, while under financial pressure, they’re being asked to vote to convert themselves from owners back into customers.

There’s no denying, too, that for-profit private ownership necessarily compromises the social objectives of the body being privatised. As with the privatised industries, there will be some ‘regulation’ – like the veto on shirt colours – but, as recent events at Leyton Orient have made clear, football clubs are overseen as if they are small businesses rather than vital community assets.

“There is no such thing as fan ownership. There are individual chairmen and chairwomen, and there are families like the Glazers.”

There’s no going back, either. With a sale like this, not only do you lose control of the direction of the club, but, unless it goes bust again, you’re never going to be able to buy it back at a price you can afford. When you privatise your club, you sell it now and forever. Your children, or their children, will never own a stake in it.

But what’s the alternative? To be in perpetual fund-raising mode to stop Fratton Park collapsing? To tolerate years, maybe decades, in the lower leagues watching irresponsible owners of other clubs buy titles and burn through cash like jet fuel in their private planes?

Well, maybe. Because there is no good alternative here. Football is so monstrously unfair that, even when you’ve been chewed up and spat out the other end by rogue owners, it can look like there’s no other choice but to try again and hope for better.

And what a risk it is. Not every bad owner looks like a second-hand car salesmen. Many of the worst, especially US owners, were rightly celebrated for their business acumen. Shad Khan invented a new type of bumper that sits on virtually every truck in America. Stan Kroenke sneezes, pisses and farts $100 bills. Even poor, wretched Randy Lerner ran a business worth $35bn. Sadly, then, being wealthy is no guarantee of anything. These days, almost everyone who owns a sports team is rich – and most of them manage their teams badly.

If football was better run – run more financially equitably, with the long-term interests of clubs at heart – then we’d have a centrally administered league fund (topped up with Premier League TV money), offering long-term, low-interest financing for supporter-owned clubs to rebuild their grounds.

But, there isn’t. As with so many pressing issues, the FA is absent, too busy arguing itself into irrelevance. The EFL, meanwhile, has made it perfectly clear whose side it is on in the battle between fans and owners.

So there’s respectable, back-breaking poverty or there’s buying a ticket in the club owner’s lottery and hoping things work out this time.

Personally I’d rather wait it out, cut my cloth, live from season-to-season. Easy for me to say, of course. I haven’t been through all that Portsmouth fans have. I don’t have to find the money to keep the club running while we wait for the football bubble to explode and bring the bad owners back to earth.

The situation reminds me of the scene in Catch-22 when Joseph Heller plays out the old parental complaint that, “If someone told you to jump of a cliff, would you do it?”

Yossarian, horrified by the war, tells his superior officer that he won’t fight any more. “But, Yossarian,” the Major replies, “suppose everyone felt that way.”

“Then,” said Yossarian, “I’d certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way, wouldn’t I?”

And that’s the trouble. Deep down I believe Portsmouth fans selling out is a terrible, terrible mistake.

But what else are they to do?

What use is it to stand alone against the madness of modern football?*

*The idealistic answer, of course, is this: you’ll always be able to look yourself in the mirror and know you did the right thing. You’ll know that everything you have, you earned. And you’ll know that maybe, just maybe, your stand inspired others.

Being brutally honest, football fans need this. We need you to prove it can work, because, if it can’t, our best hope of sorting football’s problem out ourselves vanishes.

Fans up and down the country who’ve never done a thing for you, need you to walk the hard path so that, when others follow later, it’s that little bit easier. So that supporters who didn’t lift a finger when Pompey ran into trouble can point at your club and say, “If they can, why can’t we?”

That’s what’s on offer. The opportunity to fight a battle you didn’t ask for, a battle you might lose.

And, in return, you won’t get a thing. Not financially, anyway.

But you will get esteem, pride – eventually even a little glory. You’ll get a chance to show that football can be different – and better. You’ll prove that football clubs – like all the things in life that really matter – aren’t for sale.

Have I sold it to you, yet?

Oscar Wilde said, “No good deed goes unpunished.”

For football’s sake – and Portsmouth’s – I hope he was wrong.

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this, please buy my book “The Ugly Game: How Football Lost Its Magic And What It Could Learn From The NFL”. That way I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.

Pingback: Portsmouth Football Club ownership – the fans must now decide | A 'one click' guide to Pompey ownership