The co-owner of Morecambe was barred from acting as a solicitor in May after a blistering report into his conduct, but the EFL refuse to comment on why they were happy for him to remain in charge of the club.

Between June 2016 and March 2018, “a member of a prominent, foreign royal family” paid €9.4m into the client account of a British law firm. That money, which was earmarked for the purchase of a Ferrari Aperta, a Ferrari FXX-K and a Bugatti Chiron, subsequently vanished, leaving the client [Client A] without any cars and down more than €8.3m. The person running the London office of the firm and centrally involved in the deal was Colin Goldring, who just a few months later, in May 2018, became a co-owner of Morecambe with Jason Whittingham and, after that, a director of failing rugby club, Worcester Warriors.

Following a complaint from Client A in 2019, an investigation was launched by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) which concluded in May 2022 with a ruling from the Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal. The owner of the law firm was struck off. Mr. Goldring, who was not a qualified solicitor, was issued with a Section 43 order – an indefinite bar on an unqualified person working as or for a solicitor.

There is no suggestion Goldring committed any criminal offences, but the ruling does not make for happy reading.

Findings of the tribunal

The Tribunal was roundly critical of Goldring’s conduct, saying his “actions had related to a considerable financial loss which harmed a client and damaged the reputation of the legal profession” and that the Section 43 order was necessary “for the protection of the public.”

In its findings, the Tribunal said:

“Mr Goldring had been the person with conduct of the transactions which were the subject matter of the allegations relating to Client A.

“Mr Goldring admitted amongst other things that he had caused or allowed the improper provision of a banking facility to Client A and that he caused or allowed the payment of monies totalling up to €8,310,780 from the Firm’s client account to third parties, without Client A’s knowledge and/or informed consent.

“He had also failed to exercise the required due diligence and fulfil certain anti-money laundering obligations.

“In respect of [another client], he admitted that he signed an endorsement on a settlement agreement, falsely and misleadingly purporting to confirm that he was ‘a relevant independent legal advisor (as such term is defined in section 203 of the Employment Rights Act 1996)’, when he was not.

“He admitted that he breached amongst other things the requirement to act with integrity in doing so.”

These were the headline failings. Beyond that, the Tribunal also heard that:

“Mr Goldring’s files were characterised by a lack of documentation. They were without transfer authorities, client care documentation, and due diligence documentation.”

In signing a statement saying that he was a “relevant independent advisor”, Goldring “failed to act with moral soundness, rectitude, and steady adherence to an ethical code.” His action “in this regard was, at best, manifestly incompetent.”

The SRA has 10 principles which it expects solicitors to follow. The ruling found that Goldring failed to uphold 7 of them. Which means he failed to:

2. act with integrity;

4. act in the best interests of each client;

5. provide a proper standard of service to [him] clients ;

6. behave in a way that [maintained] the trust the public [placed] in [him] and in the provision of legal services;

7. comply with [his] legal and regulatory obligations and deal with [his] regulators and ombudsmen in an open, timely and co-operative manner;

8. run [his] business or carry out [his] role in the business effectively and in accordance with proper governance and sound financial and risk management principles;

10. protect client money and assets.

The aftermath

After the ruling was made public in early July, Goldring put out a statement through Morecambe and Worcester saying, among other things, that the ruling related “to Colin’s work as a trainee solicitor in 2017.” It went on to say that “it is regrettable that failings were found at the firm I was working for, as a trainee, which impacted some work I did for a client. The outcome delivered by the SRA acknowledges the lack of appropriate supervision provided to me as a trainee solicitor.”

It also says that, “[the ruling] cleared me of any allegations of dishonesty or lack of integrity and did not impose a fine or ban. The outcome was agreed on the basis I had acted with honesty and integrity. I hold these values in the highest regard and am glad my name was cleared on both.”

Having read the ruling, it’s hard to feel that the statement reflects the full gravity of the situation. It makes no specific mention of any the legion of personal failing by Goldring, but rather, as I read it, positions him as a junior party to someone else’s failings.

Legally and morally, the buck stops with the owner of the firm. And it’s true that Goldring was a trainee solicitor at the time – not the ranking officer – but like being a “junior doctor” that doesn’t mean a trainee is just the teaboy. Mr Goldring had joined the firm in July 2015, when he was 31 years old, negotiating a deal where he received 80% of the fees he brought in.

So, while it’s true to say he was a “trainee solicitor,” the actions which were the subject of the complaint occurred while he was in his early- and mid-30s and after he had worked in the legal field for many years. (As early as January 2010, when he became the director of a now closed company, he gave his occupation as “lawyer”.) Indeed, the ruling says, “Mr Goldring was not a trainee fresh out of law school which was a fact accepted on behalf of Mr Goldring.” Goldring did not leave the law firm until 2019, more than six months after taking over at Morecambe, so I don’t think the conduct covered in the ruling can be regarded as ancient history.

It’s also true, however, that Goldring was not found to have acted dishonesty; the charge was withdrawn during the proceedings.

But his claim that he was “cleared” of acting with a lack of integrity is one I find harder to understand. As it says in the ruling, “[The SRA’s barrister] emphasised that Mr Goldring admitted that his conduct lacked integrity.”

His claim that he wasn’t fined is correct. But the statement omits mention of him having to pay £13,000 towards the Tribunal’s costs.

His claim that he was not barred is also puzzling to me at first glance. Perhaps it’s that, because he was never a qualified solicitor, he wasn’t struck off. Or perhaps it’s because he agreed to the punishment, he doesn’t regard a ban as having being imposed.

Regardless of how you interpret the ruling, though, Goldring can never work as or for a solicitor, including exactly the kind of work he was doing at the time, without SRA approval. This may not technically be a ban, but I think many people would, taking the everyday use of the term, understand it that way.

I asked Goldring to explain the claim that he hadn’t been barred or had any finding against his integrity, but he did not respond.

I should reiterate at this point that there is no suggestion that Goldring broke any laws in any of this.

The Owners’ and Directors’ Test

Having read the ruling (which is something I’d recommend to anyone; it’s only 34 pages long and clearly written), I was struck by what a catalogue of failings it contained. How, I wondered, could anyone possibly remain the director of a football club after this?

Morecambe had obviously anticipated this, including a paragraph in their statement saying, “The EFL and the RFU were made aware of the situation prior to the order being agreed. All regulatory bodies expressed to Colin that they were satisfied he was fit and proper to own and be director of a sports club.”

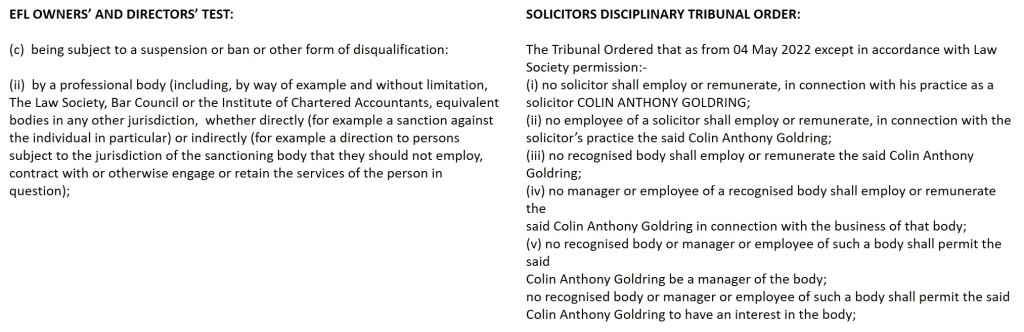

Given the ruling and the EFL’s own regulations, this surprised me. The EFL’s Owners’ and Directors’ Test (ODT) includes a number of a “disqualifying conditions” – things that bar you from owning or running a club. One of these covers, “being subject to a suspension or ban or other form of disqualification: (ii) by a professional body (including, by way of example and without limitation, The Law Society, Bar Council or the Institute of Chartered Accountants, equivalent bodies in any other jurisdiction.”

I assumed that being barred by the SRA from practicing as a solicitor would be a clear example of the above, even if he was not a fully-qualified solicitor at the time. Especially as, immediately after this, the ODT specifies that this applies, “whether directly (for example a sanction against the individual in particular) or indirectly (for example a direction to persons subject to the jurisdiction of the sanctioning body that they should not employ, contract with or otherwise engage or retain the services of the person in question).”

The wording here is strikingly similar to the Tribunal’s order which says, among other things: “no solicitor shall employ or remunerate, in connection with his practice as a solicitor COLIN ANTHONY GOLDRING.”

Elsewhere in the regulations, however, it says that clubs must not allow someone who “is subject to a Disqualifying Condition either [to] become a Relevant Person or (if he was already a Relevant Person before the Disqualifying Condition arose) to continue to be a Relevant Person for the Club, for so long as the Disqualifying Condition subsists unless permitted by an order of the League or the League Arbitration Panel.”

In other words, the EFL retain the discretion to disregard a disqualifying condition. (Although how this determination would be made is unclear.)

Which means that for Goldring to continue to own Morecambe either his Section 43 ban didn’t count as a disqualifying condition or it did disqualify him and the EFL decided to let it pass.

Which was it? I contacted the EFL and they stonewalled, refusing to comment on “individual circumstances” and suggesting I get in touch with Morecambe instead. This I did, with a range of questions about Mr Goldring’s conduct leading to the ban, about his statement and about his understanding of where he stands in regard to the ODT. I did not hear back from him before his announcement this morning.

At the same time, I asked the EFL to confirm hypothetically if a Section 43 order from the SRA would be a relevant ban from a relevant body. They refused to answer, instead sending me a link to the ODT – the very web page from which I had quoted in my initial email.

Like a broken comb

The situation, then, is that the co-owner of an EFL football club was found to breached seven of the SRA’s ten principles, in a case where upwards of €8m of client money went missing, where he admitted a range of failings, including failing to act with integrity, and where the regulator described his conduct as, “at best, manifestly incompetent” and barred him from practicing law, “for the protection of the public” and the EFL won’t even say if this conduct is a breach of the ODT or not.

It seems to me that, if this ruling doesn’t rise to the level of a disqualifying condition then the ODT is even more toothless than we thought. If it does, and the EFL decided to waive any sanction, then the EFL have some very serious explaining to do.

Or they would’ve had had Goldring and Whittingham not thrown in the towel today, presumably to focus on their rescue efforts for Worcester Warriors. (While they both resigned from Morecambe Football Club.Limited on Saturday 3rd September, they remain co-directors and -owners of Bond Group Investments Limited, the company through which they own their 80% share of the football club. And so they remain, at least for now, both subject to the ODT. I’m not holding my breath for any action from the EFL, who will be hoping any sale doesn’t drag on too long.)

Goldring’s and Whittingham’s impending departure is a lucky break for the EFL and, hopefully, for Morecambe. But it’s hard not to feel this is yet another deeply unsatisfactory chapter in how English football clubs are owned and run.

***********************************

Update: on 10th September it was reported by The Telegraph that the EFL had not signed off on Goldring’s claim that they had known about the SRA ban and approved his remaining in charge at Morecambe. If this is so, and the EFL was simply unaware of the SRA findings and Goldring’s questionable statements about them, then it would be negligence on an extraordinary scale. Had Goldring simply gambled – correctly – that no one at the EFL would even bother to read the findings of the Tribunal? If so, it raises questions about the competence of the organisation in performing even basic administrative functions.

When I contacted the EFL on 11th September seeking to establish when the organisation first knew of Goldring’s ban and his statement that they were happy that he remained fit and proper, they refused to comment.

***********************************

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this piece, please buy my latest book: No Questions Asked: How football joined the crypto con. That way, I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.