Last month, Crusaders fans voted to sell the Belfast club to Irama, a Singapore-based company. When I tried to ask the new owner some basic questions about its business, it threatened legal action. Which of course immediately made me wonder: who is Irama, where does its money come from and what can Crusaders fans expect of their new owners? Come with me and let’s find out…

“Dirty and unfriendly. Cockroaches in the room. Mould in the bathrooms. Unhelpful staff.”

“Awful, Filthy, Smelly, Unclean hotel accommodation.”

“Pathetic, awful, disgusting. The furniture in the rooms looks like it’s been picked from a garage sale and the bathrooms have mould everywhere.”

These are representative extracts from TripAdvisor accounts of staying at The Claremont Hotel in Singapore. With 370 reviews, it had an average rating of 2.0. I’d give my wheelie bin a better score than that.

The hotel was owned by Parvinder ‘Perry’ Chopra, the British man who owns Irama, as well as several yachts and now 70% of Crusaders FC. For a time, the hotel was even the registered office of Irama.

Chopra put the property up for sale in 2016, asking for more than £50m, but it appears not to have sold. It went back on the market in 2019, this time with a price tag of a little below £40m, selling eventually for a touch over £38m. Decent money for what one guest had described as the “worst hotel ever.”

It’s not the only hotel the Irama backers have owned, however. And not the only one that has sometimes failed to delight paying guests.

The Claremont Hotel in Kissimmee, Florida, also scored 2.0 on TripAdvisor before it closed for renovation in 2014. The last review is headlined, “Nastiest place ever!!!” and includes the claim that, “the outside and the pool had trash and dirty diapers everywhere.”

Shortly before the closure, the hotel was reported to have served eviction notices on residents and then shut off electricity and hot water to the rooms. This was in late January when, presumably, it is cold even in Florida. “We don’t know where to go or what to do,” a resident was quoted as saying. The hotel manager was reported as claiming the electricity hadn’t been cut off on purpose by the owners, but by the power company over an unpaid bill – until it was pointed out that the reception area still had electricity.

WHAT HAPPENS IN VEGAS

The Claremont in Las Vegas, which has also closed, wasn’t on TripAdvisor. But it was on Google Reviews, where it too got a pasting from guests, scoring just 1.6 out of 5. “Stains in the carpet and blood on the bathroom floor,” said one reviewer. “Found neat things in cabinents,” said another. “Razor blades, screw driver, gum, drug parifanalia, duct tape.” Must’ve been one hell of a stag do.

There’s also a Claremont Hotel in Cannes: 2.5 stars on TripAdvisor. “I was given a cell that had never been cleaned!” said a reviewer. “It had a shower cubical not fixed to the floor a sink the tap came off and no toilet!” On the plus side, given the hotel’s proximity to the marina – a five-minute walk – you might almost be able to see Irama’s two yachts, whose home port this is, from the window of your cell.

THE IRAMA EMPIRE

The pattern seems to have been that parts of the group bought up struggling hotels and then ran them as cheaply as possible while seeking planning permission to upgrade them. Sometimes they’d do this work themselves, sometimes they’d flip the property for a profit. Later they’d do something similar with more than half a dozen nursing homes.

Nothing here – or, spoilers, anywhere else in this piece – is illegal. But it does make you wonder if the Irama philosophy might be a little more Mike Ashley than Sheikh Mansour.

Beyond the hotels and care homes, there’s also a small airport in Maryland and “Lagpat,” an electrical components retail business in Singapore and the US. (More about that later.) The group also owned a flying school in Florida and half a dozen companies in the UK, many in property development, presumably from before the founder moved to New York. Perhaps it was this UK activity that enabled the initial acquisition of The Claremont in Singapore, for what must’ve been a substantial sum.

The US property development business (“The Claremont Group”) no longer has an official web presence and nor are there any confirmed photographs of Chopra online – which I think must be a first for a UK football club owner – but an archived version of the company’s website from 2013 introduces it thus: “The Claremont Group is in the business of acquiring real estate in depressed markets around the World. We are 10 years old this Year and with all the skill sets within the group we are ready to take on more acquisitions in Niche market sectors, more than we have ever acquired within a short period of time.” An inspiring mission statement, to be sure.

Now TripAdvisor doesn’t do property development reviews, but I wonder what it might make of some of Claremont’s US projects.

ARRESTED DEVELOPMENTS

In 2011 – the same year the Group bought the Claremont Hotels in Vegas and Kissimmee – it bought a hotel in Atlantic City, aiming to complete a full renovation. Some work was apparently done, but the project soon ground to a halt. Claremont eventually sold the building in 2018, but as late as October 2019 it was just a boarded-up shell.

In 2013, Claremont bought a historic building in Cincinnati: the 16-storey Ingalls Building, which was the world’s first reinforced concrete skyscraper when it was put up in 1903. The company was reported as planning to invest up to $8m to convert it into 50 condos. But, just two years later, it scrapped the plans and sold the building, saying it was too busy on other projects.

At one point, Claremont was reported to owe $120,000 in property taxes on the building – now paid – and had supposedly failed to get tax credits to support the development project. But the company still made a tidy $2m profit on a building it had owned for just two years and seems to have spent very little money on.

In 2013, Claremont also bought a former hospital in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, which was being used as offices. According to a piece in The Citizen’s Voice & Sunday Voice ($), a local paper, Claremont was intending to convert the property into a 250-bed assisted living facility – the first of five such projects they were planning. Within a year, things seem to have gone south, though, with a former employee of the hospital telling the Standard-Speaker ($) that the business had been closed, with all staff terminated by email. She said, “I was laid off along with every other administrator nationwide and with no warning, feeling like one of the biggest victims of their false plans and promises. The city wasn’t the only one given false hope,” she said. “We were all conned.” The paper noted that Claremont had failed to take up a request for comment on the story – something they again did when I asked about the Hazleton project.

The same year, Claremont bought a care home in Texas. Three years later, the building was condemned and the company forced to sell it. A similarly inglorious fate awaited a care home in Ohio, which was bought in October 2013 at auction. Following a fire in 2018, which destroyed the building, the property was put up for sale again.

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

Which brings us to the Claremont Hotel in New York. The Group bought the property, which was being used as a Caribbean cultural centre, in 2011. Costing $2.5m, the site is on W58th Street, a short walk from Columbus Circus and just a stone’s throw from some of the most expensive apartments in the entire world.

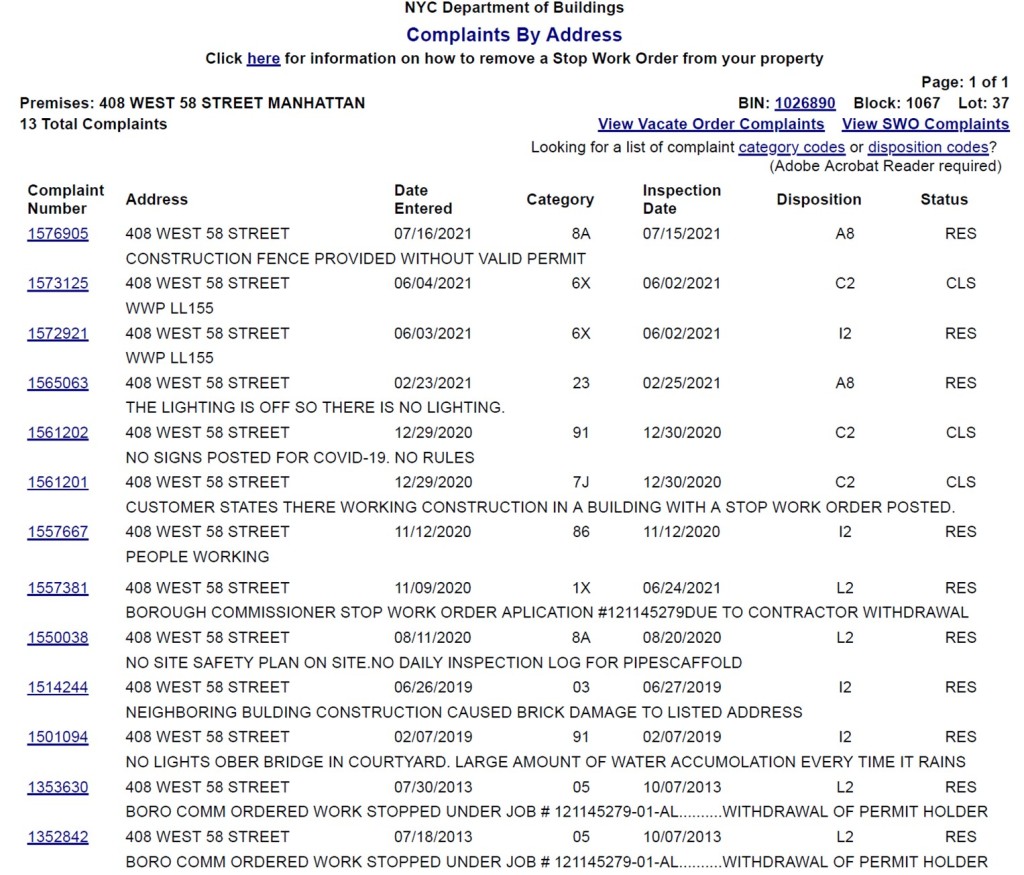

According to planning documents, the original idea was to turn the four-storey townhouse into a six-storey apartment block. Things have not gone smoothly to the extent that, eleven years later, the project is not yet complete. Work was halted in 2020 by the borough commissioner citing “contractor withdrawal” and noting that “0%” of the work was complete and the site needed to be made safe.

During the project’s lifetime, a number of complaints have also been lodged with the New York City Department of Buildings.

What exactly went wrong isn’t clear, but in April 2021, Denal Construction Corp filed a suit against Claremont in the New York County Supreme Court claiming over $440,000 in unpaid bills for construction work on the property from January 2020 to October 2020. Claremont denied the claims and filed its own counterclaims, including that Denal was knowingly overcharging Claremont, something that Denal has in turn denied. (This is not the only time the group’s companies have been to court. In 2014, a UK business called MeterTech Limited was set up to sue British Gas for patent infringement after buying two US companies that owned some smart meter IP. The registered UK director of the company was also the general manager of the Claremont Hotel in Singapore. MeterTech lost the case.)

There’s a website with a holding page for the W58th Street property, which seems to suggest it will be finished soon. Also on the site is a link to a second property in Cannes, which seems to have been renovated into a high-end rental – like a luxury AirBNB – and, to be fair, it does look pretty swish. So, perhaps that’s the plan for the New York building when it’s finally finished.

THE ENGINE ROOM

Claremont didn’t take out a mortgage at the time of the Manhattan purchase in December 2011, or at least there is no public record of it, so we assume it was a cash purchase. However, in subsequent years, Claremont took out numerous mortgages on the property through an investment firm. Over time some of these have been paid off, but the four outstanding mortgages totalling $4.5m were consolidated into a single charge in 2019 and assigned to a Singapore firm – Lagpat. In other words, Chopra’s electronics retailing business in Singapore appears to have financed the still-incomplete eleven-year build to the tune of $4.5m. Because it’s based in Singapore, Lagpat’s accounts aren’t publicly available, so it’s hard to assess its size, but clearly it must generate a significant profit.

On one industry directory site, Lagpat is listed as having 201-500 employees. But, looking around, only one US-based employee is readily Googleable and LinkedIn has just two people with Lagpat as their current employer, both based in Singapore. This is lower than I would expect for a business with several hundred employees worldwide. I also found several old Claremont-related company websites for US businesses, all of which were registered by one of the two Singapore-based Lagpat staff. The Claremont staff member who seemed to be acting as hotel manager during the Kissimmee blackout also turns up in council minutes in a Texas town as the named Claremont contact for a care home redevelopment, though he was then said to be living in Las Vegas. It begins to look, then, like an empire with a very compact core team.

Quite where this leaves Irama’s overall financial strength is unclear, but as yachts, hotels and care homes aren’t cheap, we must assume that some of the businesses have done very well. (If US states and Singapore would force companies to publish their accounts, making sense of this would all be very much simpler.)

What we can fairly say, I think, is that, based on publicly available information, it seems to be the case is that, over the last ten years, Irama’s US sister companies have embarked on a series of ambitious real estate projects, often on decaying buildings, and a number have stalled pretty badly. Doesn’t mean there haven’t been finished developments, of course, and no real estate developer plans for a 100% success rate with their projects.

So where does this leave Crusaders FC? Well, it seems that the fans have sold 70% of their club to a man with virtually no digital footprint and a business empire whose size and structure is pretty unclear.

As I said, none of this is remotely illegal or dishonest. And there’s no suggestion that Irama is seeking to acquire Crusader’s land for the purposes of real estate development – which, judging by the company’s track record, might be considered good news.

RUSH JOB

None of this, though, brings us any closer to understanding Ian Rush’s role in Irama. As I previously reported, despite being described as a “substantial shareholder” in Irama, Rush doesn’t own a stake in the company. (Chopra holds its only share.) Rush’s name also doesn’t appear on the Land Registry entries against Irama’s three UK football grounds. (Those are 100% owned by Irama and bought for nearly £1m cash although, according to the company’s own and rather strange wording, Ian Rush owns 20% of Irama’s real estate in Crusader’s “by agreement.”) It was these questions that preceded the legal threats from Irama, though there’s no suggestion Ian Rush was aware or approved of Irama’s actions.

What we can reasonably assume, though, is that Rush is no mere figurehead in this deal. Irama representatives supposedly told Crusaders’ fans that Rush and his wife would occupy two of the six seats on the new Crusaders board. The remaining four spaces have apparently been earmarked for two Crusaders’ fans representatives along with Chopra’s son and a fourth, as yet unidentified, Irama nominee.

Rush is, of course, an all-time great of UK football, but his post-retirement CV features a spotty managerial career and no great executive experience. He has never run a football club, let alone one like Crusaders, which is both large by Northern Irish standards and yet small by those of English football. (There are non-league clubs in the English pyramid with higher playing budgets than Crusaders.)

What qualifies Ian Rush’s wife, a singer and model, to sit on the board is even less clear to me, though that may be a product of my relative ignorance about the details of her career.

DECISION-MAKERS

Which brings us to Chopra’s son, the person who will likely, in the absence of his father, be the key decision-maker at the football club. His role is important because Chopra supposedly explained to Crusaders fans that Irama’s interest in football was substantially related to his son’s mental health problems, which had followed the stalling of his football career. (Now in his mid-20s, Chopra’s son was released from a large football club’s academy before drifting into non-league football.) I wouldn’t normally bring up personal information like this, but feel justified in doing so because Chopra has repeatedly given this as an explanation for his desire to invest in football when selling people on his plans.

In one sense, this is admirable: a chance to give something back and sketch out a better, kinder youth development path, one that recognises that most football dreams must inevitably go unfulfilled.

But it does tend to position Crusaders not as a priceless and unique community asset, but rather a project that a wealthy US-based businessman has financed for his son by buying a club to which neither had any prior personal affiliation.

All in all, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to wonder whether Irama’s ownership may bring both a cash injection and a net loss of footballing expertise. And, if business in the US is any guide, we probably shouldn’t expect Crusaders to be building a new stadium to rival Spurs’ nor competing with City to sign Erling Haaland.

Stepping back, we might also wonder what of any of the above is so problematic that Irama threatened to take legal action against me even for asking question about the business. (The company has also sent a legal threat to footballing campaigner (and the co-author of my recent book) James Cave, for having reported about their clodhopping entry into English football. I am also aware of a number of other individuals who have received legal letters for commenting on Irama.)

Is there more to come out about Irama? Or is it merely the case that Crusaders fans ought to prepare themselves for being owned by an opaque, litigious company, with a history of running fleapit hotels and unfinished real estate developments?

How’s that going to work out, I wonder? Because I have news for Irama: if you don’t like being emailed polite questions by journalists, wait to see what happens the first time the team loses five games in a row. Those hotel reviews are going to look like Valentine’s cards.

************************************

I contacted Irama with a long list of questions about its associated businesses and the projects detailed in this piece, but it did not respond.

A special thanks to “Bat Shrew,” a Shrewsbury Town fan in New York, whose brilliant research unearthed much of the corporate information in this piece. Without their amazing work, this story would not have been possible.

************************************

Update: In September 2022, Irama’s attempt to buy Crusaders collapsed when it emerged that the change in status from a fan-owned, not-for-profit organisation to a for-profit limited company would make the purchase liable to corporation tax. Facing a potential tax liability of several hundred thousand pounds, Irama pulled out of the deal.

************************************

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this piece, please buy my latest book: No Questions Asked: How football joined the crypto con. That way, I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.

The below article is behind a paywall but the takeover has hit problems:

https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/sport/football/irish-league/crusaders/crusaders-fighting-to-keep-big-money-takeover-alive-as-share-proposal-scheme-hits-legal-complications-41906669.html