Year two of Shaun Harvey’s B Team revolution is coming to a close. But has it been any more successful than the first?

When the EFL announced B Teams would be admitted into the EFL Trophy, it promised great things. The opportunity to see the stars of the future would revitalise the tournament. Fans and money would be drawn inexorably to the chance see Premier League fringe players get the valuable competitive experience they needed to break into the first team and, eventually, the England side. It was a flawless plan.

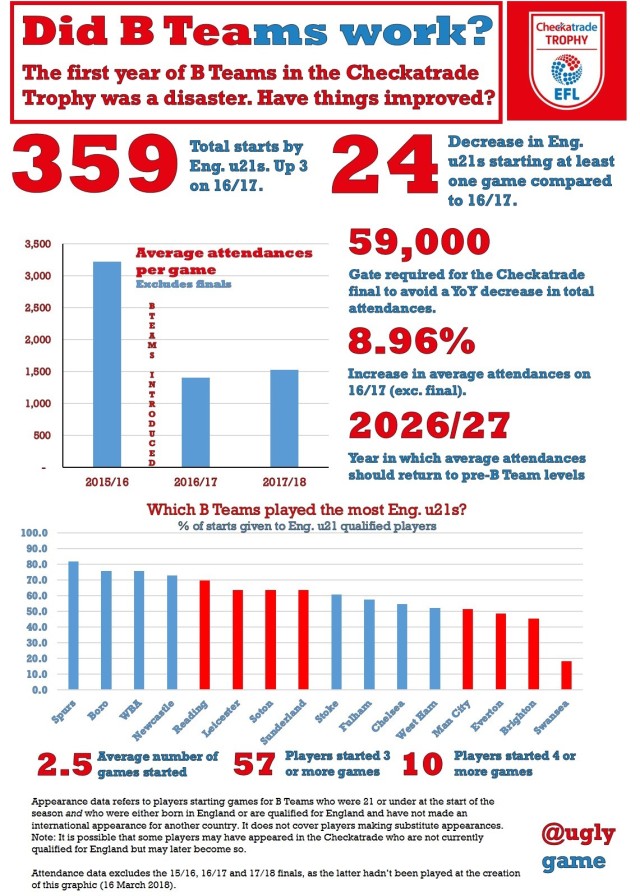

A selection of numbers and shapes arranged in garish colours.

Of course, we know it didn’t quite work out like that. Many of the bigger teams declined to enter, while others used the competition to give run outs to old timers. Unenthralled by the sight of Peter Crouch and Charlie Adam invading what had been a perfectly respectable lower division competition, fans stayed away. Average attendances fell by more than half and as I chronicled here the structural flaws of the competition meant very few young English players got meaningful game time. The killing blow is due in May, when Half Man Half Biscuit release a new album with a track titled, ‘Swerving the Checkatrade’.

“Don’t tell me, it’s National Shite Day”

But if we know anything about English football, it’s that complete and total failure is no reason to stop doing something. And so the EFL duly reupped the Checkatrade for another two years, tweaking the format to create more local derbies and giving the tournament a big marketing push.

And so here I am again, back with the numbers you wouldn’t need if Shaun Harvey would just admit it isn’t working.

Attendances

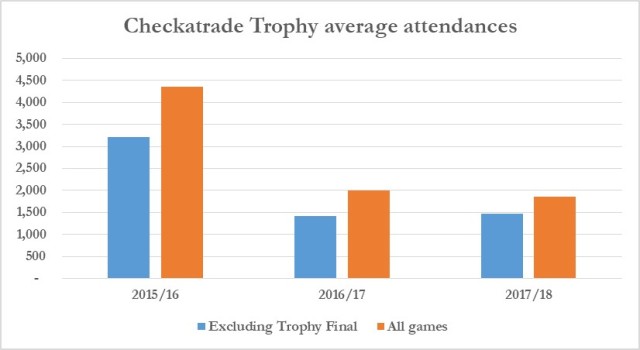

Let’s start with the good news for the EFL: attendances have crept up. On a year-on-year basis, and excluding the final, average attendances are up 8.96%.

Friday Night and the Gates Are Low

That’s right, having implemented a format that caused a greater than 50% fall in average attendances, the full might of the EFL’s brightest minds has managed to drive attendances back up slightly. In case you were wondering what 8.96% means in actual punters, it’s moving from an average of 1,404 fans a game to 1,530. In other words, the EFL has managed to get an extra 126 fans per game in. Bravo, Shaun!

If growth continues at this rate, we will only have to wait until 2026/27 for average attendances to exceed those of 2015/16, the last year before B Teams. Think of the party we’ll throw.

“I don’t know where I’m going

Only God knows where I’ve been”

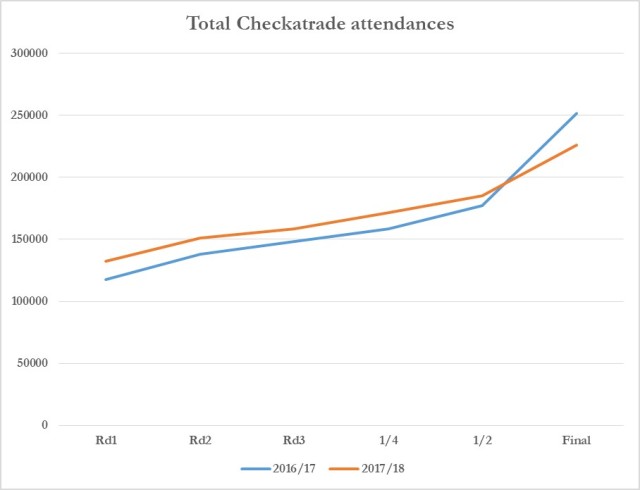

There’s a fly in the ointment, however. Last season’s Checkatrade figures benefited from a greater than 74,000 turnout for the final as Coventry and Oxford, two of the larger sides in the lower divisions, faced off. The EFL tendentiously promoted the huge gate as evidence that fans were coming round to the format.

It’s awkward, then, that this season’s final, featuring Lincoln and Shrewsbury, is likely to be significantly less well-attended. Doubtless the EFL will rush out a statement accepting the blame and acknowledging that permanent damage has been done to the prestige of the competition.

The below graph shows cumulative attendances for this season and last season. With such a modest increase year-on-year, an attendance of less than 59,000 for this year’s final, which seems a definite possibility, will mean that total attendances actually fall this year.

[Update: And lo it came to pass. The Final drew 41,261 fans, meaning that total attendances in 2017/18 were 226,138 – down from 251,367 the previous year.]

Dead Men Don’t Need Season Tickets

What needs to be said, too, is that with many clubs offering promotions and, in some cases, free tickets, it’s not certain that total paying admissions aren’t actually down this year. All of which helps explain the unreported scandal of the EFL secretly promising to cover the losses any teams might make in hosting games.***

Game time for young players

As with attendances, the picture is broadly the same as last year, with a few bright spots for the EFL, but little to parade around at a press conference.

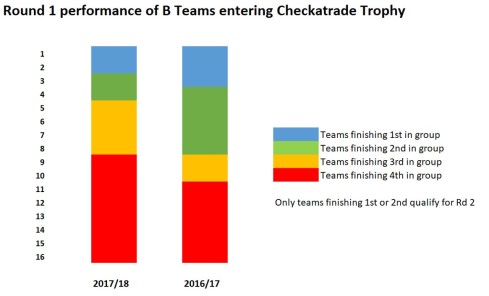

The structural problems with the format were again an issue. Put simply, B Teams did much worse this year. Despite a stronger group of entrants, just four of 16 B Teams finished first or second in their group and qualified for the next round. Eight B Teams – one half of the total entrants – finished bottom of their group. This compares with last year when eight of 16 B Team finished first or second in their group and qualified for the next round.

Reasons to Be Miserable (Part 10)

And so, despite Chelsea’s Future Loan Stars making it to the semi-finals, the total number of games for B Teams fell from 61 to 55. (This is in line with my analysis last year that 2016/17 produced an unusually high number of games and shouldn’t be relied on for future planning.)

As a result, the opportunities for young players to get games were reduced.

Before I give you the figures, let me tell you what I was counting. I noted all the starts made for B Teams by England-qualified players who were 21 or under at the start of the 2017/18 season. That means players who were either born in England or are qualified for England and have not made an international appearance for another country. It does not imply that they have or will represent England, just that they could.

For simplicity, I’ll refer to these players as ‘young English players’ or ‘England u21s’. The figures don’t cover players making substitute appearances. Nor do they include those starting for EFL teams – since these wouldn’t be incremental appearances enabled by the presence of B Teams in the competition. In other words, they would’ve played any way, just as Ethan Ampadu did for Exeter last year before moving to Chelsea. (Note, finally, it is possible that some players may have appeared in the Checkatrade for B Teams who are not currently qualified for England but may later become so.)

With all that established, the total number of starts by England-qualified u21s rose by 3 from 356 to 359 – with a per game rise from 5.8 to 6.5. Given that there are 380 Premier League games a year, the entire development output of the Checkatrade Trophy this year amounted to less than the equivalent of just one additional start by a young English player in each PL game.

I Was a Teenage Armchair Honved Fan

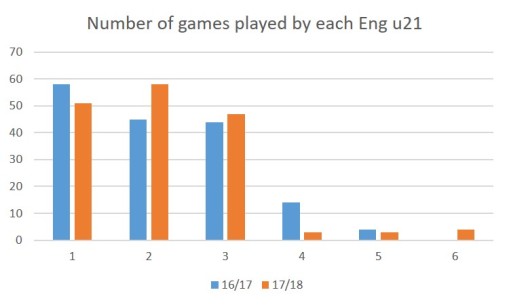

The total number of young English players appearing for B Teams actually fell from 165 last year to 141, which seems to be a reflection of Chelsea’s run in the tournament and an effort from a number of B Teams to field stable line ups. And, not only did fewer young English players get experience in the Checkatrade, but fewer of them played 4 or more games. In fact, the average England u21 in a B Team made just 2.5 starts this year.

As I said last year, it seems like an awful lot of faff just to get a few youngsters a few extra games. I struggle to believe that these extra games will make any measurable impact on the confidence, experience and readiness of players.

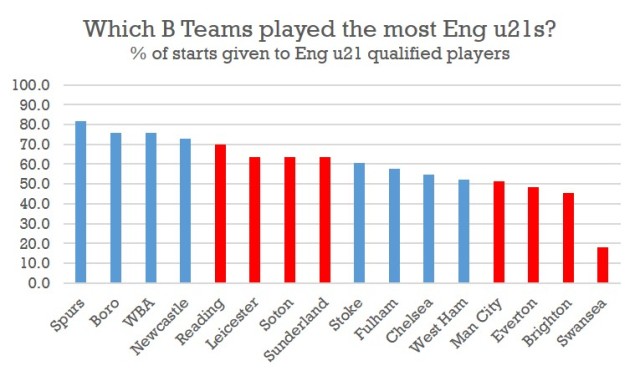

In total, the percentage of total possible starts made by young English players in B Teams was 59.3%, which means that for every 11 players starting in B Teams, six-and-a-half were English u21s. This was a rise of 6 percentage points on last year. In other words, B Teams did make an effort to field more of the players that this tournament is supposed to help develop.

The average reflects considerable variation between teams, however.

“I’m a colt in your stable

I’m what Harry Kane was to Abel”

Generally speaking, there seemed to be an inverse relationship between the size of the club and the number of young English players they fielded in their B Team. So, while Boro, West Brom and Newcastle fielded the most England u21s, Chelsea, Everton, Man City and West Ham were all near bottom.

At this point, special mention needs to be made for Tottenham, who had more than 80% of starts made by England u21s. Essentially, 9 of every first 11 were England u21s. For Man City, it was five-and-a-half.

Once you’ve quantified the number of young English players turning out, you have to ask if these appearances are good quality ones and if they are material to the players’ career development.

I’d argue that playing against weak EFL sides in front of almost empty stadiums could never be regarded as properly competitive games. These can’t provide the experience of playing in a pressure setting against motivated opposition in front of a baying crowd.

As you know, these last 12 months have been remarkably successful for the England youth teams. I checked and of the 55 players who started for England in the u21 Euro Semi, u20 WC Final, u19 Euro Final, Toulon Final and u17 WC Final, just 14 played a game in the Checkatrade last year (2016/17). Those 55 players made a total of 319 senior appearances last year, only 29 of them in the Checkatrade. That’s 9% of their total football.

So, while there is no doubt that the England youth teams (for whatever reasons) are having a remarkable run of success, the Checkatrade has been a very small part of it. The large majority of England’s most promising young players have not played in the competition and are playing most of their football in other settings.

“Lord I never drew first

But I drew first blood”

In my view, the largest problem with youth development is the unreasonable expectation that any amount of coaching and development can prepare young players to step effortlessly into a Premier League first 11 and immediately outperform seasoned pros. Almost no young players arrive readymade and Wayne Rooney-like, able to dominate games from the off.

And yet, with managers getting the sack less than a year after winning the title, some of the Big 6 seem totally unwilling to blood their young stars.

Instead, we have a development philosophy – of which the Checkatrade is the most absurd element – which reverses the development burden. As FA Technical Director, Dan Ashworth, said, “The players have got to prove to the managers they are good enough to compete in the Premier League.”

Only a senior football executive could fail to spot that this is common sense standing on its head. It is the Premier League who must prove they deserve to keep monopolising England’s best young players.

What does it all mean?

Broadly speaking, it’s as you were. The flaws in the competition, which were apparent to everyone but Shaun Harvey before the relaunch, remain. Fans don’t like it. It doesn’t create many games for young English players and what games it does create are of dubious value.

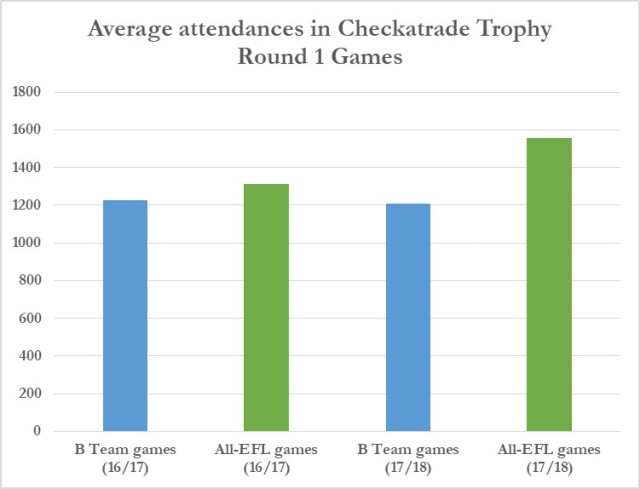

The clearest evidence of its unpopularity isn’t even the fall in total attendances. It’s what happens if you compare attendances in first round games between all-EFL team ties and first round ties involving a B Team.

“Let me make my final stand”

Ties involving B Teams showed a marginal decrease in average attendances, while all-EFL team ties showed a substantial increase in attendances, probably as a result of the efforts to create more local derbies. As fans of the competition have said all along: people would much rather watch a derby with a lower league rival than a group of 20 years from a different footballing universe.

As a football competition, then, the Checkatrade is continuing to fail, and its sustainability must continue to be in question. For all the EFL’s revitalising work, the trophy is perhaps better now considered as a series of friendlies paid for by the Premier League.

But will all this stop Shaun?

Why would it? Abject failure has never stopped league football’s chief gunslinger before, nor punctured his self-belief. All we can do is hope that, somewhere among the EFL’s largely supine owners, there lurks a Pat Garrett.

Until then, better saddle up and prepare for yet another unwanted Young Guns sequel.

Martin Calladine

If you enjoyed this, please buy my book “The Ugly Game: How Football Lost Its Magic And What It Could Learn From The NFL”. That way I’ll have the money to write more things you might like. Oh, and please spread the word, too. Thanks a lot.

*** The unreported scandal is this: Before the vote on this season’s renewal, the EFL changed the Checkatrade competition regulations and introduced, for the first time, a right for it to compensate teams making losses from hosting games. The wording of the regulations made this seem like a right it reserved, rather than a promise. However, ahead of the vote, the EFL issued private guidance to the clubs assuring them that, provided they promoted the competition actively, and refrained from disparaging it, the EFL would guarantee to cover any losses.

And so, with the competition now a one-way bet, the clubs reupped the completion format that fans hate.

It’s not clear at this stage how many, if any, clubs have availed themselves of this financial support. One has to wonder, however, why this facility should be necessary if the competition is, as the EFL asserts, a success. Further, I’d like to know why the EFL is promoting to its members a format it has reason to believe will lose them money.